Inbreeding

What is inbreeding?

Inbreeding is the process of mating genetically similar organisms.

In the animal and plant world it's a common proces. If we associate inbreeding with humans, we call it incest. But in the human world as we know it today, incest is not a social accepted proces anymore. But in human history, incest was something that has happened more frequent and in some ancient cultures totally accepted. Even in western cultures it was something that happened in ancient history.

Inbreeding itself is generally considered as being something negative, but it can also offer some positive effects.

When two closely related organisms mate, their offspring have a higher level of homozygosity: in other words, an increased chance that the offspring will receive identical alleles from their mother and father. In contrast, heterozygosity occurs when the offspring receives different alleles. Dominant traits are expressed when only one copy of an allele is present, while recessive traits require two copies of an allele to be expressed.

Homozygosity increases with subsequent generations, so recessive traits that might otherwise be masked may start appearing as a result of repeated inbreeding. One negative consequence of inbreeding is that it makes the expression of undesired recessive traits more likely. However, the risk of manifesting a genetic disease, for example, isn't very high unless inbreeding continues for multiple generations.

The other negative effect of inbreeding is the reduction genetic diversity. Diversity helps organisms survive changes in the environment and adapt over time. Inbred organisms may suffer from what is called "reduced biological fitness".

But inbreeding has also identified potential positive consequences as already mentioned before. Selective breeding of livebearers has led to new strains. It can be used to preserve certain traits that might be lost from out-crossing.

Influences of inbreeding in wild forms of viviparous livebearers versus influences of inbreeding in breeding forms of viviparous livebearers.

As breeders of livebearers, we often have to deal with inbreeding. Usually our aim is to maintain or strengthen certain properties. Like to set up a new guppy line for example. Or to keep certain traits in line breeding in certain wild forms of livebearers. But also because certain species are rarely offered and are therefore difficult to obtain in order to add fresh blood to a certain species in order to keep the species strong and the quality high, which is known as “inbreeding depression”. All reasons to use inbreeding...

It is a known fact that if no fresh blood can be added to an existing group, the bloodline can become weaker after a certain number of generations. This can eventually manifest itself in weaker health, thin specimens, faded colors and pattern, lesser fertility or deformed specimens.

However, I have to say that if I compare wild forms with breeding forms of livebearers, my own experience is that with breeding forms a weakness seems to appear sooner than with wild forms. Again, that weakness may be a weak system, deformities, emaciation, or even a short life. What exactly it's stuck on, is merely the question. I have regularly asked other serious breeders what their experiences are with regard to inbreeding in both wild and breeding forms. And then it turns out that people have similar experiences. So, I have my own vision about what could be the basis of this. Of course, this is speculative but based on experience. Well, I I have searched here and there for articles or papers on this subject, but did not really come back with a satisfactory reply. What I can glean from certain articles is that (and from my own experience) livebearers in the wild are less susceptible to mutation in comparison to such fish which are kept in captivity. Now those mutations in the wild are more focused on mutations caused by external influences and not so much by inbreeding. Because in a smaller environment the chance of inbreeding is greater than in a large group in the wild.

Inbreeding can lead to high health problems in many species of live animals because the resulting reduction of heterozygosity levels in offspring, negatively influences and diversifies health-related traits (described by Charlesworth D & Charlesworth B, 1987; Frankham *Ralls, 1998; Keller & Waller, 2002).

Now the concept of “inbreeding” can be taken quite broadly or quite narrowly. Inbreeding is of course a fact that takes place within the same bloodline. But that does not only have to concern sister/brother, father/daughter pairings, but also niece/uncle, aunt/nephew, grandfather/granddaughter, etc. So lines that are already somewhat further apart. And in last case, we're talking about inbreeding to linebreeding.

The fact that in the wild within populations matings occur between closely related relatives as well as distantly related relatives, which makes the gene pool diverse, is generally good for the quality of the species. Or there must be another population nearby that mixes with one population to keep the gene pool diverse.

In August 2015, an article was written about female Trinidadian wild guppies being able to recognize family members. But won't be averse to mate with a family member. It is stated here that the conclusion drawn was that they only mate once with the same family member and should the same family member make another attempt that the female will reject him. For this study, a group of virgin females and a group of non-virgin females were used. Young virgin females were found to be receptive to random mating partners (i.e. related and unrelated). This seems to have to do with giving young virgin females the confidence of their reproductive potential. Non-virgin females seem to be more selective in their choice of mating partners because they are already reproductively assured. The research has shown that the non-virgin females mate with both unrelated and related fish, but again only mates once with the same family member in a related relationship. On the other hand, this is not the case with virgin females which get involved with the same family member. The context of recognizing relatives in female non-virgin guppies is therefore in the moment of mate choice. This recognition is also called “kin recognition”. Kin recognition provides an important mechanism to prevent or contain inbreeding by enabling individuals to recognize and actively discriminate against relatives during mate selection. Kin recognition also seems to occur in other live forms, from micro organisms to mammals.

One option is that female guppies recognize individuals through previous encounters that they recognize as relatives and will then avoid these individuals.

Another option that is described (Hepper, 1986; Hauber & Sherman, 2001; Penn & Frommen, 2010) is the possible existence of a “template matching”. This means that an individual possesses an internal “kin template” and identifies conspecifics as being related or unrelated.

The term “template matching” is used to summarize 3 possible mechanisms, i.e. (Hepper, 1986; Hauber & Sherman, 2001; Penn & Frommen, 2010):

- A genetically based template (recognition alleles).

- A template learned by self-inspection (self-referential phenotype matching).

- A template learned by observing the phenoype(s) that share relatedness (family-referential phenotype matching).

The research also shows that the above template matchings are only conclusions and not factual evidence. However, it is considered to be very plausible.

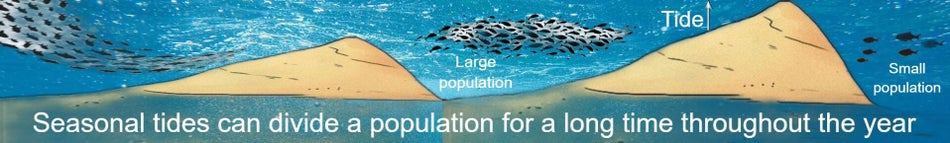

The already mentioned inbreeding depression also occurs in the wild. Imagine, a certain area has certain water tides during certain seasons, more inbreeding can take place in a closed area if a group is separated from the rest of the population by the tide, as a group will be in a closed environment with fewer fish .

Whether the same applies to other livebearers is the question, but also with regard to this group I can say from experience that the wild forms that I keep and have kept have little to no physical deformations compared to their breeding forms after so many generations.

The study further revealed that Trinidadian female guppies have a promiscuous mating system with a sequential choice of mates. The gene pool (gene variation) is diverse and therefore less influenceable on the degeneration of their physical condition. So that the species remains strong after all these years within the same bloodline. But also in the wild, guppy populations will show multiple phenotypes, because of the diverse gene pool besides the environmental influences. This goes also for more livebearer species in the wild.

Good examples of good strength and quality of wild strains are actually research strains (lab strains). Those strains have been owned for decades with little to no fresh blood and the descendants of each generation are virtually free of degeneracy. But this is also clearly visible in home breeding, counting from the first catch from the wild and the descendants that were scattered on it, which are still in good shape at many breeders.

Left photos: A lab strain of wild guppies "Smaragd iridescens (Sm/Ir), 1927.

Collector: Prof Øjvind Winge, Kopenhagen University.

Year of collection: 1927

Photo courtesy by Harry Wallner.

If we look at breeding forms, there are too many focal points in line breeding in which there are few till no new triggers present in the gene pool to promote gene variation (for a stronger bloodline). Even wihen a breeding form is put into line breeding, things go well for the first few generations, but after that it will be noticeable that degeneration appears to be the order of the day if there is no further interference of fresh blood.

Above: This diagram is suited for all living specimens.

And what's also important is that not all livebearers (wild and breeding forms) are equally strong when it comes to bloodlines. But if we compare wild livebearer populations to their breeding forms, it seems that the wild forms are way stronger than the breeding forms. But also when a breeding form seems to be closer (in bloodline) to the wild form, the stronger they are.